Blancpain’s Fifty Fathoms made a splash in the 1950s and 1960s, then vanished like a sunken sub for a generation. Now it has risen again in style.

In 1956, a movie called The Silent World made a lot of noise. The movie was a documentary that chronicled the deep-sea expeditions of the French oceanographer Jacques Cousteau in the Mediterranean and Red Seas, the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. It was a cinematic tour de force, one of the first films to show the underwater world in color.

The Silent World holds a unique distinction in movie history: Not only did it win Hollywood’s highest honor, the Oscar, for Best Documentary Feature at the 1956 Academy Awards; it took France’s highest prize, too. It was the first of only two documentaries ever to win the Cannes Film Festival’s prestigious Palme d’Or. (The other was Michael Moore’s Fahrenbeit 9/11 in 2004.) The Silent World remains the only documentary ever to win both an Oscar and the palme d’Or.

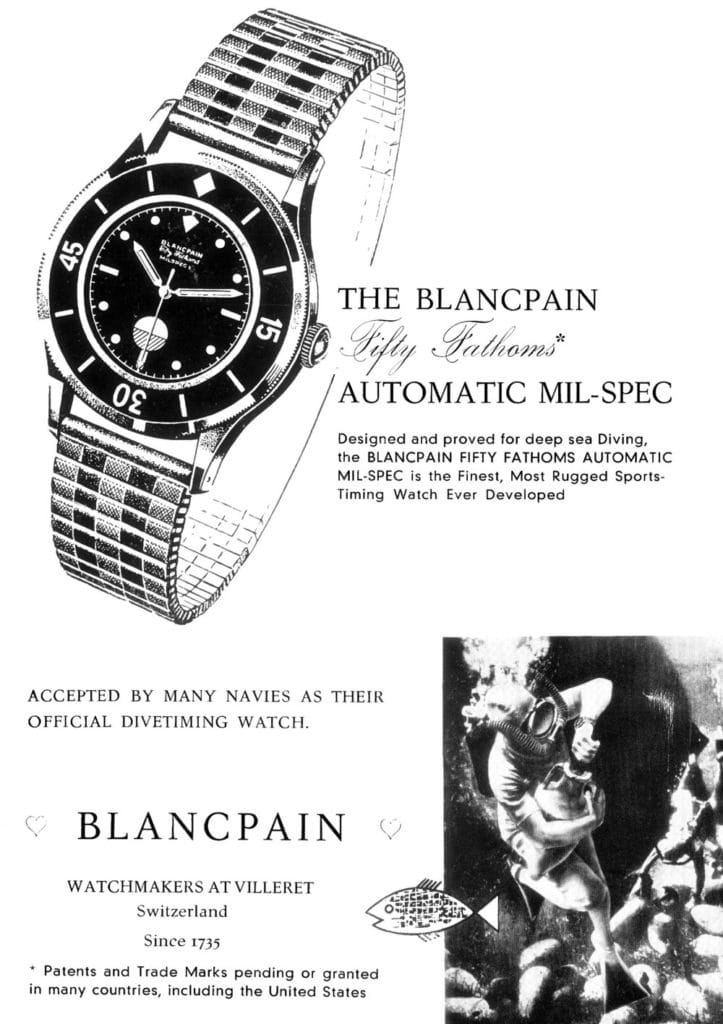

The Silent World launched a new generation of stars. There was Cousteau himself and his ship, Calypso, both of whom would become environmental icons. There was Louis Malle, the 24-years-old Frenchman who co-directed the film, and went on to fame directing both French and American films. And there was the rugged, handsome watch with the black dial and bezel that appears throughout the film on the wrists of Cousteau and his divers both above and below water, the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms.

Its command performance in The Silent World seemed to destine the Fifty Fathoms for horological stardom. It had appeared on the watch scene three years before in 1953, the same year as the Rolex Submariner. The two watches are recognized as the first modern divers’ watches. In their wake came such noted divers’ watches as the IWC Aquatimer, the Eterna Kon-Tiki and the Breitling Superocean. By the end of the decade, a slew of watch manufacturers had introduced into their lines a divers’ watch with the features, benefits and, in many cases, the dark, masculine looks of the Submariner and the Fifty Fathoms.

But while the Submariner went on to become a diving-watch icon, the Fifty Fathoms sank into oblivion. In a cruel twist of fate, the Blancpain company and brand disappeared during Switzerland’s quartz crisis of the 1970s; with them went the Fifty Fathoms. It remained submerged in its own silent world for more than 20 years.

In the past decade, however, the Fifty Fathoms has resurfaced. Blancpain, which for the past 16 years has been part of Switzerland’s Swatch Group, the world’s largest watch conglomerate, has rediscovered and revived its dive watch pioneer.

The company marked the 50th anniversary of the Fifty Fathoms in 2003 with a limited-edition series of watches (150 pieces total) that now fetch the full price plus a premium on the aftermarket. Last year, Blancpain unveiled to wide applause its first Fifty Fathoms collection, consisting of three watches, including the first Fifty Fathoms flyback chronograph and the first Fifty Fathoms with a tourbillon. The comeback is the latest twist in the series of ups and downs that is the Fifty Fathoms saga.

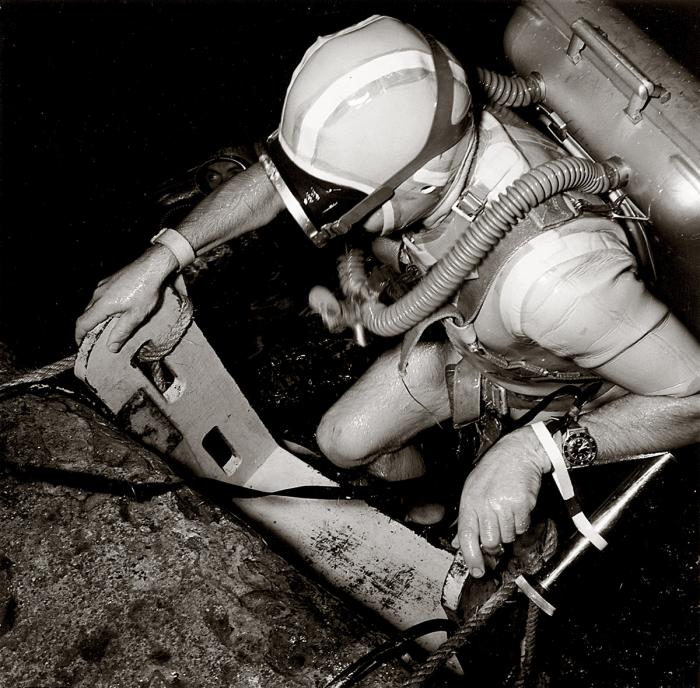

The Fifty Fathoms story begins in 1952, when the French Ministry of Defense instructed a French Navy captain, Robert Malubier, to create an elite unit of navy combat divers. Malubier and his assistant, Claude Riffaud, sought to equip the members of the unit, called “Les Naguers de Combat” (French for “combat swimmers”) with a superior divers’ watch as part of their official equipment. They reportedly approached the Lip Watch Co., France’s top watchmaker at the time, about producing an extremely water-resistant watch, but Lip turned down the project.

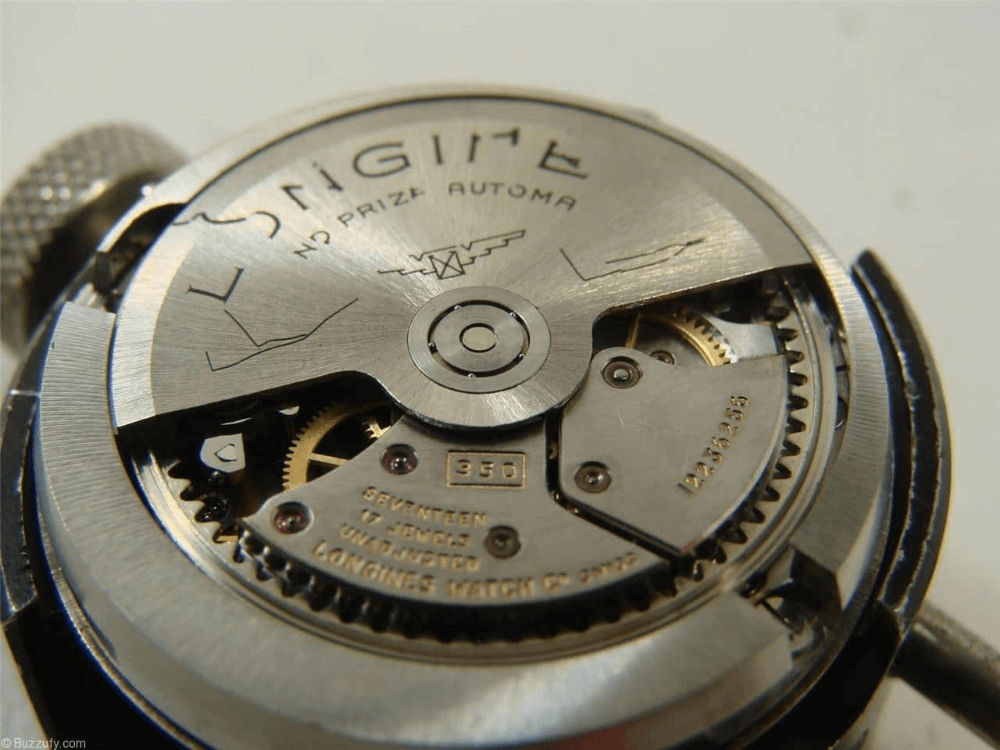

Malubier and Riffaud then turned to a Swiss watch company, Blancpain Rayville S.A., based in the Jura Mountain village of Villeret, where the firm was founded in 1815. (The company began using the Rayville name after the seventh and last generation of Blancpain family owners sold the firm during the Great Depression in 1932. Rayville is actually a phonetic anagram of the name Villeret.) Using specifications drawn up by the French officers, Blancpain Rayville developed the Fifty Fathoms. Delivered in 1953, it had a robust, stainless-steel case, with water-resistant guaranteed to 91,45 meters (or 50 fathoms, hence the name).

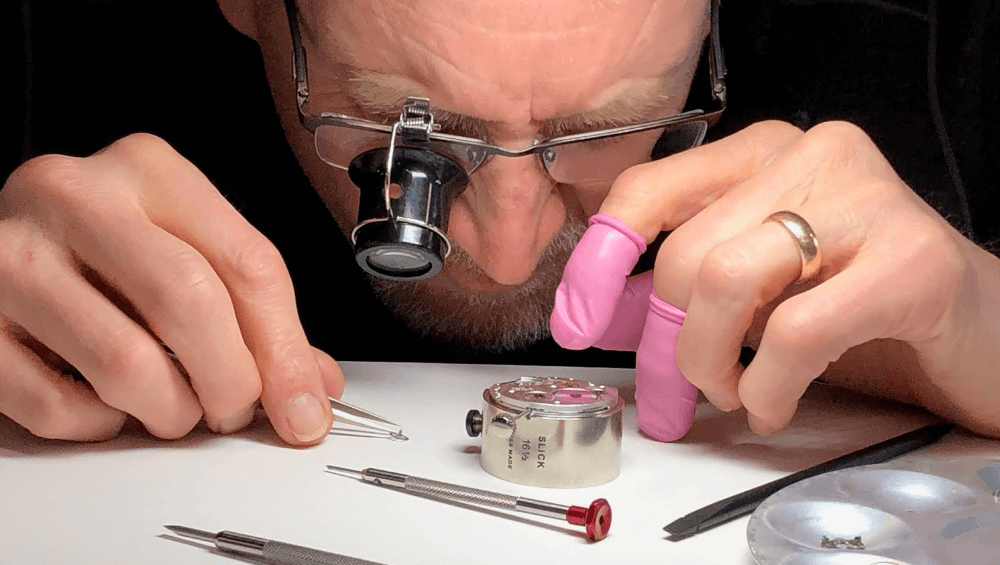

That depth was the maximum depth recomended for a scuba diver. The watch contained an automatic movement, which reduced friction on the winding stem. For greater visibility in the dark, it had large luminous numerals and markers that stood out against the black dial and bezel. It also had an epoxy bezel that rotated in one direction only. The unidirectional construction was a precaution against the bezel, which indicated the dive time, being accidentally jolted, resulting in a false and potentially dangerous reading.

The watch was a hit with the French combat divers. Soon Cousteau, who was a captain in the French Navy from 1948 to the late 1950s, began using the watch in his undersea explorations. The watch’s role in The Silent World boosted awareness of it and it was adopted by a number of military organizations for their divers, commandos and Special Forces units. In addition to the French Navy, the Fifty Fathoms was used by German, Czech, Polish, and Israeli forces, as well as by the U.S. Navy Seals. It was also sold commercially starting in France.

Ironically, it was sold there by Lip, who had turned down the opportunity to make the watch, under a marketing and distribution agreement with Blancpain Rayville, since it had no distribution in France. The watch remained popular throughout the 1960s. It was the watch of choice for no less a diving authority than Lloyd Bridges, star of the popular American TV show “Sea Hunt”, which portrayed the adventures of an ex-Navy frogman turned freelance scuba diver. Bridges appeared on the cover of the February 1962 issue of Skin Diver magazine wearing the Fifty Fathoms.

Despite its popularity, the seeds of the Fifty Fathoms’s demise were sown the year before. In 1961, Blancpain Rayville SA was acquired by SSIH, one of Switzerland’s largest watch groups at the time. SSIH (for Societe Suisse pour I’Industrie Horlogere) was formed in 1930 when the Omega and Tissot companies merged to weather the difficulties of the Great Depression. (The historical SSIH should not be confused with the contemporary SIHH – Salon International de Haute Horlogerie – the watch exhibition held annually in Geneva.)

Blancpain was one of a legion of independent firms, mostly Swiss like Lanco and Marc Favre, but also including Hamilton in the United States, that were taken over by SSIH in the 1960s and 1970s. By the early 1970s, according to Omega historian Marco Richon, the SSIH group was the top watch producer in Switzerland. It owned 50 companies, with 7,300 employees, producing 13.5 million watches, for annual sales exceeding 700 million Swiss francs. The group’s unrivaled superstar was Omega, by far Switzerland’s best-known and best-selling Swiss watch in the post-World War II period. Tissot was the group’s second most important brand. The rest, including Blancpain, were at best bit players.

As an SSIH subsidiary, Blancpain Rayville continued to produce Fifty Fathom watches throughout the 1960s. At some point in the 1970s (sources vary as to the exact year), with demand for mechanical watches on world markets plummeting as a result of the arrival of new ultra-accurate quartz analog and digital watches from Japan, SSIH decided to close the Blancpain Rayville operation. Omega took over the production at the factory in Villeret and the Blancpain brand became dormant.

No doubt SSIH in the mid-to-late-1970s, awash in increasingly obsolete mechanical movements, was happy for the few military orders for the mechanical Fifty Fathoms that still trickled in. There are reports that SSIH continued to supply a few Fifty Fathoms into the early 1980s. Inevitably, though, the trickle dried up and production stopped.

In 1982, Blancpain miraculously came back from the dead as a producer of mechanical watches. But the Fifty Fathoms did not come with it. The divers’ watch would stay locked and neglected in Davy Jones’s locker for another 15 years. The reason, explains Jean-Claude Biver, the man who famously revived Blancpain, is that a mechanical sports watch did not fit the image of the new Blancpain that Biver was building out of the ashes of the old. Shortly after leaving Omega in 1981, he and a partner, Jacques Piguet, a member of the famous Frederic Piguet watchmaking family, bought the rights to the dormant Blancpain name from SSIH for a pittance, reportedly SF18,000.

Their idea, considered completely cockamamie at a time when quartz watches were dominating global watch sales, was to position Blancpain as a producer of high mechanical watches. They moved the firm to Le Brassus in the Vallee de Joux, where they had access to mechanical movements from Frederic Piguet, and began to position Blancpain, in Biver’s words, as “the living museum of the past.” Using the now famous advertising slogan “Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be,” Biver positioned Blancpain as the champion of mechanical watch technology.

He set out to create a series of high mechanical Blancpain watches that encompassed what he called “the six masterpieces of the watchmaker’s art,” namely an ultra-slim watch, moonphase watch, perpetual calendar watch, split-second chronograph, tourbillon and minute repeater. Reviving a dive watch from the 1950s was not a priority in the larger struggle to revive not just a dead mechanical watch brand but the nearly dead 400-year-old tradition of mechanical watchmaking. “The goal was for Blancpain to become the reference in mechanical watchmaking,” Biver explains. “We had to master the six masterpieces of the watchmaker’s art. There was no question of going into another line as long as we were developing the six masterpieces. That took some time. Once the six masterpieces were done, we had the intellectual freedom to go into the Fifty Fathoms.”

In fact, even after Blancpain mastered the six masterpieces, the Fifty Fathoms remained on the back burner. In 1991, Blancpain presented all six masterpiece watches as a single collection. In that year it proved its masterpiece watches bona fides beyond any doubt when it introduced the remarkable “1735” wristwatch, which incorporated all six masterpieces in one watch. In 1992, Biver and Piguet made a fortune when they sold Blancpain back to the successor of SSIH, SMH Ltd., now called the Swatch Group. Biver remained with the Swatch Group in various capacities, including as head of Omega and Blancpain, until 2004. He turned over the operation of Blancpain to curent CEO Marc Hayek, grandson of Swatch Group chairman Nicolas G. Hayek, in 2002. Today Biver is CEO of Hublot SA.

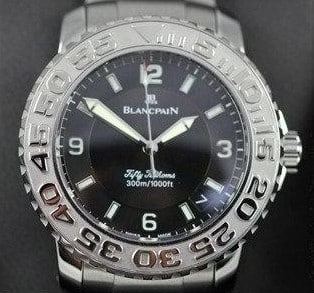

When, after a 20-year absence, the Blancpain Fifty Fathoms finally reappeared in 1997, it was a decidedly soft relaunch. It reappeared as part of a trio of sports watches with bold bezels for use on land, sea, and air that Biver called the Trilogy. It consisted of the GMT watch (land), the Fifty Fathoms (sea) and the Air Command chronograph (air). The new Fifty Fathoms had a stainless-steel case water-resistant to 300 meters (or 165 fathoms). While Blancpain did not make a lot of hoopla about the return of the Fifty Fathoms, it was at long last back in production.

In 1999, Blancpain introduced new versions of the three Trilogy watches in a limited series called Concept 2000. Each of the watches, including the Fifty Fathoms, featured bezels, crowns and pushers made of carbon-fiber-reinforced rubber. The watches came in stainless-steel, rose-gold and platinum versions, each combined with rubber. Another limited-edition series included perpetual calendar versions of each of three watches.

It was not until 2003, on the occasion of the watch’s 50th anniversary, that the Fifty Fathoms got the spotlight to itself. Mark Hayek unveiled a new 50th-anniversary edition of the watch. It had the same dial and same oversized numerals and markers as the 1953 original as well as a 40.3-mm stainless-steel case water-resistant to 300 meters. It came with a steel bracelet and interchangeable rubber strap. The big difference in the new model was the bezel: it was made of scratch-resistant black sapphire and, most notably, was not flat but curved, to give it more protection against rough surfaces.

It was powered by the self-winding Frederic Piguet Caliber 1151 movement with 100 hours of power-reserve. Blancpain produced only 150 pieces of the anniversary watch. They sold out quickly, and once again the Blancpain portfolio was without the Fifty Fathoms. There ensued, according to Marc Junod, president of Blancpain USA, a drumbeat of demand from watch aficionados and jewelers for an unlimited edition of the watch with a larger diameter.

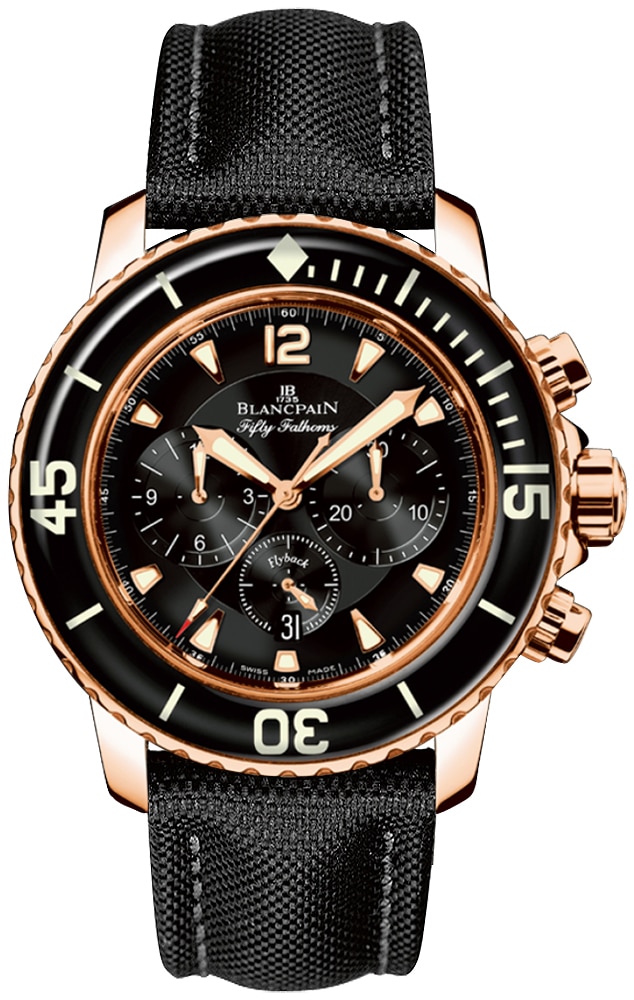

Blancpain responded to the call last year with the Fifty Fathoms collection of three watches, none of them limited editions. The collection has the DNA of the 55-year-old original, plus some new features. The cases are larger, with diameters of 45 mm, are water-resistant to 300 meters, and have crown guards. Like the 50th anniversary edition, the watches have curved bezels made of scratch-resistant sapphire.

The highlight of the Fifty Fathoms Automatique (also called the “three-hand”) is its movement. It is the first Fifty Fathoms powered by an in-house Blancpain movement, the automatic Caliber 1315, based on the hand-wound Caliber R0 unveiled in October 2006. The Fifty Fathoms Chronographe Flyback features a system of special joints in the case that make the pushers water-resistant so that the chronograph can be operated underwater. It comes in either a stainless-steel ($13,700) or rose-gold case ($24,800). The Fifty Fathoms Tourbillon is the only watch in the collection with an exhibition back, which reveals the 234-components movement. It features a flying tourbillon, fitting for the firm that introduced the world’s thinnest flying tourbillon in 1989. The Fifty Fathoms Tourbillon comes in either rose-gold ($98,200) or white-gold ($102,500) versions.

Blancpain says its intention in creating a full-fledged Fifty Fathoms collection was to give the watch “a new lease on life.” It’s unlikely that the Fifty Fathoms will drop out of sight any more. Junod notes that it now stands alongside the Villeret, Leman, Le Brassus and the ladies’ lines as a proper Blancpain collection. “There is a Fifty Fathoms family there,” he says. This year Blancpain is introducing an all-white version of the Automatique with the Caliber 1315. In the future, look for more Fifty Fathoms models featuring Blancpain manufacture movements.