Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Atmos clocks, whose ingenious, near-perpetual mechanical movements are driven by air temperature changes, have been pushing the boundaries of horology and design since the 1930s.

– Before wristwatches came pocketwatches, and before pocketwatches came clocks. All the venerable watchmaking maisons owe some debt to the clockmakers who paved the way for their portable, micromechanical wrist timekeepers, and some of them have even produced clocks of their own at some point in their history. Even today, you can find some of the biggest names in luxury wristwatches displayed on wall clocks in watch boutiques and airports – almost all of those clocks powered by electronic rether than mechanical means. However, there is one historical Swiss watch manufacture still actively engaged in mechanical clockmaking in the 21st century – applying to this ancient art the same care and meticulous craftsmanship that it devotes to its wristwatches.

Moreover, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Atmos clocks – a mainstay of the Le Sentier-based company since the 1930s – are neither electronic nor traditionally mechanical, but something else entirely. While building wrist – borne timepieces remains Jaeger-LeCoultre’s primary vocation, the company continues to release, year after year and often in limited numbers, new variations on the Atmos, an invention that traces its origins all the way back to 1928. Recent models have teamed Jaeger-LeColtre’s seasoned design team with artists such as Apple Watch co-designer Marc Newson and have boasted collaborations with world-acclaimed luxury purveyors such as Hermes, Baccarat, and Alfred Dunhill.

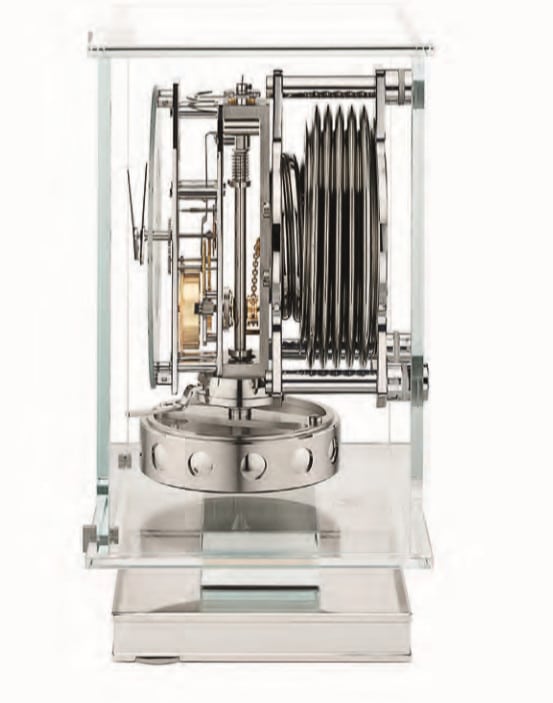

The principle behind the Atmos is simple in concept but complex in execution, especially considering the technical limitations of the era from which it arose. The clock literally runs on air, thanks to a gaseous mixture inside a hermetically sealed capsule, activating a membrane connected to the clock’s drive spring, which expands when the temperature rises and contracts when it falls. The up-and-down swelling of the membrane, like the bellows of an accordion, constantly winds the movement, and does so at a high level of efficiency: a temperature variation of a single degree (Celsius) in either direction is enough to provide the clock with a running autonomy of about two days. This is due to the extremely slow balance, which oscillates only twice per minute – compare this to the 480 beats per minute executed by a balance in a standard wristwatch caliber. The movement’s ingeniously designed gear trains require no oil, which also helps the Atmos to run accurately, efficiently and more or less perpetually (Jaeger-LeCoultre, and many who have written about the Atmos, describle the mechanism as “near-perpetual” or “virtually perpetual”).

It was Jacques- David LeCoultre who redeveloped the Atmos into what we know it as today – friendly long before that was fashionable: Jaeger-LeCoultre is fond of pointing out that it would take 60 million Atmos clocks to equal the energy consumption of a single 15-watt electric lightbuld. The patent on the technology has long since expired, but Jaeger-LeCooultre is, to this day, the only watchmaking or clockmaking firm that utilizes it.

Developing this type of “perpetual motion” clock – one that would run and stay wound without any direct mechanical or electronic influences – was lifelong obsession of Jean-Leon Reutter, a Swiss engineer, who in the 1920s brought his vision of such a device to life with a prototype whose movement reacted to the slightest variations in temperature and air pressure to constantly wind itself. Reutter called his invention the “Atmos,” because it was driven by atmospheric changes, equipping the first model with a glass capsule filled with a mixture of mercury, a substance he knew to be sensitive to such variations due to its use in thermometers, and ammonia. This glass tube was fitted into the metal bellows that powered the clock. Inside it , gas and liquid expanded and contracted with the minuscule temperature and pressure changes that occur commonly in a room, thus supplying power to constantly wind the mainspring. Reutter had the first working models of his clock manufactured by his employer, the French firm Compagnie Generale Radio (GGR).

It was this version of the Atmos (the so-called Atmos 1), so the story goes, that caught the eye of Jacques-David LeCoultre of Switzerland’s LeCoultre watch company (Edmund Jaeger and his Paris-based watch firm had yet to merge with LeCoultre and was in fact still a competitor at the time), who discovered it in a shop window and purchased it. This eventually led to LeCoultre purchasing the patent for the device from Reutter and ultimately utilizing the storied watchmaking talent at the company’s disposal to both perfect the Atmos from a technical standpoint and to use its marketing savvy to make sure that word of this amazing timekeeping innovation spread worldwide. Reutter, who was a trained engineer but not a watchmaker, had been struggling on both fronts.

The so-called Atmos 2, in which LeCoultre replaced the mercury in the capsule with a more stable, saturated gas called ethyl chloride, was released in 1936. These early models were plagued with technical issues, so full production did not begin until 1939. In the interim, specifically in 1937, Jaeger and LeCoultre merged their companies into the firm we know today, thus ensuring the Atmos clock would be known hence-forth as a Jaeger-LeCoultre product. “It was LeCoultre who redveloped the Atmos into what we know it as today.” Says Stephane Belmont, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Director of Heritage & Rare Pieces. “He designed a device that was much more compact for integrating into a clock, one that worked with only the temperature differences rather than atmospheric pressure. He figured out how to perfectly seal the clock so it was totally airtight, which was necessary for the movement to function properly. Finally, LeCoultre had to fully redesign the movement itself and industrialize its production. ” It is a testament to the Atmos’s inventiveness, its design, and Jaeger-LeCoultre’s commitment to it that the clock has been in more or less continuous production since the first ones marketed to the public in the 1930s- somewhat surprisingly, considering the toll that the advent of quartz oscillators and electronics took on both the watch and clock industries. The mechanical watch, as we all know, came roaring back after the 1970s-’80s Quartz Crisis, but mechanical clocks never really recovered, remaining a very small, niche business. Part of the reason for the Atmos’s longevity could be the prestige it gained throughout much of the 20th century as an official gift of the Swiss government to American presidents and other heads of state, a distinction it held from the 1950s through the 1980s.

“The Atmos became known as the President’s Clock,” says Belmont. “When you see pictures of presidents in the Oval Office during that era, you can usually see an Atmos somewhere in the background. Whenever a President, a Pope, or a famous actor made an official visit to Switzerland, they would receive one because it was the symbol of Swiss clock-making and savoir faire.” The roster of VIPs who have received an Atmos reads like a Who’s Who of 20th century history: Jordan;s King Hussein, England’s Queen Elizabeth and Winston Churchill, France’s Charles de Gaulle, American presidents John F.Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, American actor Charlie Chaplin, and Pope John Paul II, to name a few. The Vatican, in Belmont’s estimation, most likely claims the largest collection of Atmos clocks in the world.

Jaeger-LeCoultre has collaborated with talented designers on the Atmos since the 1970s – Of course, a clock that carries the Jaeger-LeCoultre brand must be more than just a clock, but a work of art on par with the company’s most coveted wrist timepieces. Jaeger-LeCoultre’s collaborations with talented designers to produce special editions of the Atmos are a tradition that goes back at least as far as the 1970s. German industrial designer Luigi Colani, who made hos name designing cars for Fiat, Alfa Romeo, BMW ant others, contributed the 1973 “Atmos Moderne” model, housing the Jaeger-LeCoultre 528/1 movement, with a squared, dial and blackened hands inside a sleek steel cube, an industrial look that broke from the clear cases and conventional round dials of previous models. In more recent years, some of the clocks have gotten more technically as well as artistically ambitious. To celebrate the new millennium in 2000, Jaeger-LeCoultre released the Atmos Marqueterie du Millenaire, whose Caliber 555 offered a 1,000 year calendar with month and moon-phase displays. It was housed in an Art Nouveau-infused wooden cabinet with marquetry re-creations of famous works by painter and illustrator Alphonse Mucha and executed by marquetry masters Philippe Monti and Jerome Bouttecon.

For 2015’s Atmos Marqueterle Celeste, Jaeger-LeCoultre combined the 17th-century craft if straw marquetry with precious minerals for an astronomical objet d’art of timekeeping. A moon-phase with an iridescent mother-of-pearl moon on a lapis lazuli sky is the central attraction, inside a crystal cabinet flanked by blue-tinted “meteors” that are actually wooden panels covered by layers of lustrous blue straw- dried, dyed, slit and flattened before being painstakingly applied to the panels in a manner that ensures ideal light effects on the stellar blue field. The air-powered Caliber 583 inside the clock drives a regulator-style display for hours and minutes, a 24-hour and month indication, and a perpetual moon-phase that is said to be accurate for 3,861 years; the cabinet comes from the Parisian atelier Maonia, a specialist in straw marquetry. A much larger and more famous Parisian firm, luxury leather goods giant Hermes, has partnered with Jaeger-LeCoultre on watches and other products over the years, most recently on an Atmos clock in a spherical crystal case. For the Atmos Hermes Clock, containing the 560a caliber, the two maisons turned to the glassmakers at Alsace-based Les Cristalleries de Saint-Louis, founded in 1586, to create its eye-catching cabinet using the so-called double or double overlay technique. The process, for which only a handful of master glass-makers possess the knowledge and expertise, involves layers colored layer, then cutting away the the top layers without touching the lowest ones. In the Hermes clock, this technique creates the clear, bead-like “bubbles” in the crystal globe, through which the clock’s inner mechanism can be glimpsed. Belmont, who likens these recessed circles to the dimples on a golf ball, hails the craftsmanship in this 176-piece limited edition that debuted in 2013. “It’s a technique that’s very sophisticated and very difficult to achieve,” he says, “because all those circles need to be placed perfectly around the clock, which means that the circles in the white layer need to be perfectly lined up with the other layers. It is very challenging, but the finished product is truly a piece of art.”

A modern artist who has become closely associated with the Atmos clock is Marc Newson, a former silversmith form Australia who is now renowned for his architectural and product designs. Newson, whose clients have ranged from Apple to B&B Italia to ford, for whom he designed an award-winning concept car, teamed up with jeager-LeCoultre in 2008, and the collaboration has produced three of the most notable Atmos clocks of the past decade, each of them also utilizing the glassware savoir faire of France’s Baccarat Crystal. The most breathtaking execution, and somewhat surprisingly the only one not produced in a limited edition, is the Atmos 568 by Marc Newson, which was released in 2016 and boasts an “almost invisible” crystal cabinet made by Baccarat. “Marc Newson has always been fascinated by the Atmos clock, but he originally came to us to work on the Reverso,” Belmont reveals, referring to Jaeger-LeCoultre’s most iconic wristwatch model, which also debuted in the 1930s. “He initially wanted to design a Reverso watch, but we thought the Atmos was a better fit for his style. Eventually he embraced the idea of reinventing the classical Atmos, creating an object that was about more than just ticking away the time. And the main thing he wanted was that the transparent cabinet would be made from single piece of crystal- an extremely difficult task. We searched throughout the world for a producer who could do it and the only one up to the challenge was Baccarat. It took a lot of time and effort for that product to be finailized.”

The final result is a timekeeping mechanism that appears to float freely in the air, behind a clear dial highlighted by blue transfer Arabic numerals, blue hands, a month indicator on a circular scale, and a color-coordinated display of the complete moon-phase cycle with a white moon on blue sky.

Jaeger-LeCoultre revisited the “crystal clear” aesthetic last year with the introduction of the Atmos Transparente, albeit in a more minimalist and Art Deco-esque take than the more avant-garde Newson version offers. The glass dial hosts simple, deep black hour markers and hands, and is treated with a nonreflective coating, allowing all the most stunning elements of the 217-piece Caliber 563 to shine: the large annular balance wheel, the vertical gear train, and, of course, the gas-filled bellows, the mechanized “lungs” that breathe life into it all.

As the Atmos clock nears the centenary of its invention, what new heights will Jaeger-LeCoultre scale with this versatile and still very unique timekeeper? Belmont hints that the coming years may bring an exploration of new complications as well as cutting-edge designs. “The challenge as always with the Atmos is developing additional functions,” he says. ” We developed the first moon-phase at the end of the 1990s and have slowly added others. It’s always a great challenge because the clock runs on very little energy, and there’s not much left over to power additional complications.” Ecen with these limitations, JAeger-LeCoultre has created over the years Atmos clocks with moon-phases, sky charts, regulator dials, equation-of-time displays, even an Atmos Mysterieuse “mystery clock” with a remontoir d’egalite, or constant-force mechanism. What could be the next step? “Maybe a repeater or a perpetual calendar,” Belmont mueses, “something with a bit of animation to it. The Atmos is beautiful but mostly quiet. It would be great to bring even more life to it.” Thus it appears that, for a clock that lives on air, not even the sky is the limit for what’s possible.