When talking about the birth of the first chronograph, there are many authors and spread rumours to be addressed. With regards to this, various watch Manufacturers ostentatiously rolled out dates and models with such a meticulous exactitude to leave even the most rigorous historian bewildered. Whereas, a few noted horology chroniclers alongside a handful of other experts were pointlessly pursuing that one date. In any event, we can be definite on one point: from its very beginnings this complication has been able to magnetise the attention and the passion of the world.

A few years ago, the history of watchmaking was rewritten due to the discovery of a pocket watch, which turned out to be the first chronograph ever made. In 1816, Louis Moinet, a French watchmaker and painter, completed what he called the “Compteur de Tierces”. This extraordinary instrument, which literally means “conter of thirds”, measures events to the 60th of a second indicated by a central hand. The elapsed seconds and minutes are recorded on separate subsidiary registers and the hours on a 24-hour dial. Moreover, it is powered by the first mechanical high-frequency movement that runs at an incredible speed of 216,000 beats per hour and features a zero reset function. Undoubtedly, the work of a genius ahead of his time.

Passion for games and gambling is indeed as old as Man. But most importantly, it has lifted the curtain on a rudimental – and admittedly – not so precise instrument for measuring an established length of time. Let us take a leap back into history again. In the late Eighteenth Century England, when the Jockey Club – which is still today the largest commercial organisation in British horseracing – was first established: a competition of speed and agility that required an instrument to accurately measure the arrival time of the participants.

In September 1821, the French watchmaker Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec invented a timepiece for timing horse races. In a meeting held in October of that same year, the French Academy of Sciences – presided by Antoine-Louis Breguet and Prony – reported on the invention that Rieussec had presented christening it the “Chronograph with Seconds Indicator”. 9th March, 1822: he received the patent that officially sanctioned the operating principles of this instrument that dropped a tiny spot of ink on the dial marking the elapsed time.

Hence chronos means time, and graph writing. Basically, it was a watch that “wrote” time, thus the term “chronograph” has stuck ever since. Technically speaking, the inking chronograph presented obvious inconveniences, such as marking only short periods of time. It also required frequent maintenance that entailed filling the ink tank and cleaning the porcelain dial after a use. Despite these drawbacks, it unexpectedly remained in production for a long striving to find better solutions from the start.

A key thing to pay attention to is that the chronograph has been linked to sports, ever since its birth and up to the present days. Thus, beyond exemplifying a precious and iconic object, the chronograph represents the technical landmark instrument for measuring time. In February 1822, the London-based watchmaker Frederick Louis Fatton developed an inking chronograph featuring a fixed dial system that earned him a patent. Even the master watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet two years earlier had worked on two double second chronometers, referred to as “d’observation”, anticipating the concept of rattrapante watches.

Louis Frederic Perrelet, a Swiss clockmaker established in Paris, designed a “physics and astronomy chronograph counter”, which granted him a patent in 1828. Yet again, another forerunner of rattrapante timepieces. The Austrian Paris-based watchmaker Joseph Thaddeus Winnerl presented a simplified version of a split-second mechanism, for which a patent was officially registred in 1831. Undoubtedly, the chronographs exerted a strong influence with a growing interest in the development of new innovative mechanisms, even though the results were at the moment not anywhere ready for a large-scale series production.

The turning point in modern horology design was unveiled in 1844: a London-based Swiss watchmaker Adolphe Nicole developed a system that allowed the hand to return to zero, which granted him a patent: the “cam-actuated lever”, featuring the distinguished heart shape. Still today, it holds the stage in many chronograph mechanisms. Nearly twenty years later, Fereol Piguet conceived and realised a mechanism that incorporated a reset function.

This discovery granted the Nicole & Capt manufacturer a patent, thus launching the first pocket watch displaying the three basic functions that we shall be meeting later in all the following chronographs: start, stop and reset to zero after indicating the elapsed time. At this point, the history of the chronograph stops, takes time, and waits for the next revolution to shake the very foundations of horology world.

A long time ago in the wintery nights of the First World War, the few officials that decided to leave the front lines and step down into the endless and muddly trenches, immediately understood the great drawbacks of the pocket watches. At the same time, the aviators also felt the need to read time fast and simply whilst flying their aircrafts. Thus, the birth of the first wristwatches. Obviously, the chronographs could not remain indifferent toward this “modern trend”. It is hence no coincidence that the early chronograph wristwatches were originally pocket watches “fitted” to this use, welding the lugs to the case and reprinting the indications on the dial.

However, watchmakers had to take horology design to the next level by making the movements as small as possible. In 1910, Moeris released the first 13-ligne calibres developed for small watch cases – slightly greater than 29 millimetres. Soon followed by other manufacturers such as Landeron, Lemania, Universal… Nevertheless, we are still speaking about mechanics activated by one single push piece, which sequentially controlled the start, stop and reset functions.

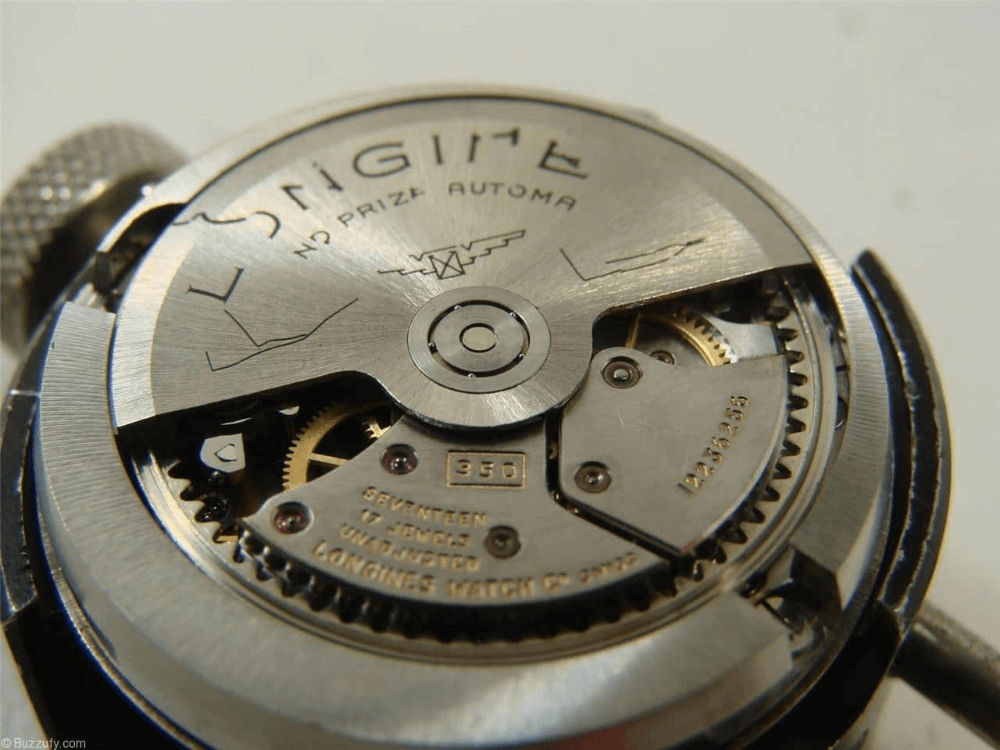

The modern age of the chronograph officially began in 1933 when Breitling obtained a patent Nr. 172129. The advertisement campaigns staged the first wrist chronograph sporting two push buttons: one for the start and the stop, the other for the reset function, which actually was an extension of a pocket watch patent registered in 1923. The modern chronograph history kicked off and started its endless quest for utmost precision and time reliability. The year 1936 welcomed a new innovation: the hand returned to zero without the need to stop the chronograph. The patent – Nr. 183262 – of this mechanism, referred to as flyback, belongs to Longines.

It was then followed up with other developments aimed to render the construction of movements easier and less expensive. To achieve this result the column wheel, which until then controlled the switching functions, was removed. In 1937, Landeron – patent Nr. 209394 registered in 1940 – released a three button mechanism, one for each single function.

From then on, the evolution of the chronographs took off with great speed, yet perfectly in keeping to the traditional standards of high-end watchmaking: manually wound or automatic movements, two push buttons, two or three subsidiary registers, column wheels and cogged gear mechanism for the transmission of energy.