How a Tokyo jeweler’s experiment in making pocket watches 84 years ago led to the creation of a global watch colossus Citizen.

In the 1920s, the young Emperor of Japan, Hirohito, received a gift that reportedly delighted him. The gift was from Kamekichi Yamazaki, a Tokyo jeweler, who had an ambition to manufacture pocket watches in Japan.

The Japanese watch market at that time was dominated by foreign makes, primarily Swiss brands, followed by Americans like Waltham and Elgin. Yamazaki felt the time might be right to begin manufacturing watches domestically that would be less expensive than the imports. To that end, Yamazaki founded in 1918 the Shokosha Watch Research Institute in Tokyo’s Totsuka district. Using Swiss machinery, Yamazaki and his team began experimenting in the production of pocket watches.

By the end of 1924, they began commercial production of their first product, the Caliber 16 pocket watch, which they sold under the brand name Citizen. The name was the brainchild of no less a personage than the mayor of Tokyo, Shinpei Goto. The mayor was a friend of Yamazaki’s. When the fledgling watch manufacturer was searching for a name for his product, he asked Goto for ideas. Goto suggested Citizen. A watch is, to a great extent, a luxury item, he explained, but Yamazaki was aiming to make affordable watches. It was Goto’s hope that every citizen would benefit from and enjoy the timepieces developed by the Shokosha Institute.

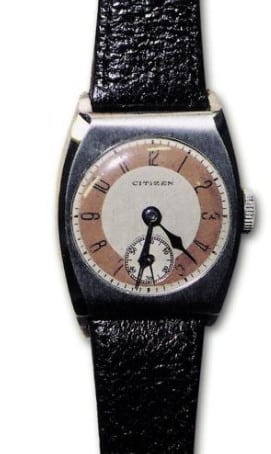

So it was that Citizen became a watch brand. It was one of these first watches, made in the European style, with the winding crown at 12 o’clock, large Arabic numerals, and a seconds subdial at 6 o’clock, that was presented to the Emperor.

The Emperor owned watches, of course, but few, if any, were made in Japan. He was said to remark at how pleased he was that he no longer had to always rely on foreign timepieces and that Japan was capable of producing watches of its own. Eventually he wrote a letter to the Shokosha Institute, praising the watch’s quality and precision.

As pleased as the Emperor was his Citizen, it would have been preposterous to suggest that the Emperor would one day see Japan become the world’s leading watch producing country, and Citizen the world’s top watch-producing firm.

But that is exactly what happened. Hirohito was still on the Chrysanthemum Throne in 1981 when Japan toppled Switzerland as the top watch producing power and in 1984 when Citizen Watch Co., successor to the Shokosha Watch Research Institute, outproduced every other watch company in the world.

This is the story of Citizen’s rise, from a small experimental producer of mechanical pocket watches, to a primary player in the quartz watch revolution that rocked the watch world in the 1970s and ’80s, to the leadership position it enjoys today in the ongoing quartz watch revolution. In 2001, Citizen produced an astounding 308 million watches and watch movements, one of every four watches made. It has fulfilled in ways that he could never have imagined Kamekichi Yamazaki’s dream of making watches available to everyone.

Auspicious start

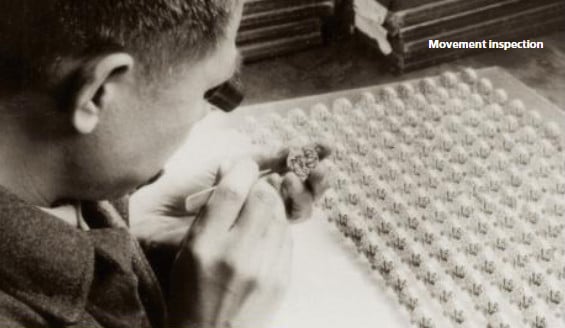

Kamekichi Yamazaki was one of a new breed of watch entrepreneurs that sprung up in Japan in the second decade of the 20th century. Japanese watchmaking was in its infancy. While Japan had mastered the art of producing wall clocks in the 1880s, pocket watches were a different story. In 1894 there were clock producers in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto and Nagoya manufacturing more than 200,000 units, but Japan had yet to produce a single watch. Hoshimi Uchida, a professor specializing in Japan’s industrial history and author of a chronicle of the Japanese watch and clock industry, explains: “The mass production of watches involved technical difficulties far greater than those in clockmaking.

Watches, with their more complicated mechanisms – balance wheels, balance springs, anchor escapements, winding mechanisms, irregular forms of bridges, and pinion staffs – required delicate machining using specialized tools smaller than the general purpose machines available for clockmaking. The machines needed for fabricating watch parts were numerous, expensive and difficult to obtain.”

The first company to take a stab at watchmaking was Osaka Watch Inc. It was a valiant effort. Osaka imported watchmaking equipment from the United States as well as eight American and two British machinists. In 1895, it produced the first Japanese pocket watches, later known as “sakameri” watches, a combination of the words “Osaka” and “American”. But watchmaking proved too challenging and Osaka Watch Inc. failed in 1902. Nippon Pocket Watch Manufacturing, another firm that began making watches in the late 1890s, suffered the same fate.

For the first two decades of the 20th century, you could count the number of Japanese watch producers on one finger of one hand: Seikosha, forerunner of today’s Seiko Corporation. Founded in Tokyo in 1893 by Kintaro Hattori, a watch and clock merchant, Seikosha began producing pocket watches the year after Osaka. But Seikosha, too, struggled with them. According to Uchida, Seikosha did not begin to make a profit on watches (its cash cow was wall clocks) until 1911, 15 years after it began watch production.

The turning point for Japan’s fledgling watch industry was World War I. The war created a business boom in Japan. It spurred the growth of Japan’s middle class; demand for watches was higher than ever before. “Clocks and watches were the first Western-style, durable consumer goods in modern Japan,” Uchida writes. As demand for watches grew, new entrepreneurs saw potential profits in watchmaking. Hattori’s Seikosha began to get some competition. By 1920, six firms had begun watch production. By 1922, there were 15.

Prominent among the newcomers was Kamekichi Yamazaki’s Shokosha factory. We know this because of a pocket watch competition staged as part of the Tokyo Commemorative Peace Exhibition of 1923. In a fascinating foreshadowing of epic watch battles to come a half-century later, it pitted the pocket watches of two Japanese producers against those of two foreign producers, one Swiss, one American. It was a David vs. Goliath matchup both ways.

The two Japanese producers were Seikosha (Seiko) and Shokosha (Citizen). Citizen clearly was in the David role. Seikosha/Seiko at that time had been producing watches for 27 years, was Japan’s leading watch producer and had even begun exporting watches to Southeast Asia. Shokosha/Citizen, on the other hand, had been in existence for a mere five years and had yet to market a single watch. Both of them were Davids, though, compared to the Swiss Nardin chronometer watch and the American Waltham they were up against. In the 1920s, the Swiss and the Americans were the world’s two dominant watch powers.

The watches were tested for three days in the physics classroom of Tokyo Higher Technical School by independent Japanese judges. Nine watches under various brands from Seikosha and three Citizen brand watches from Shokosha were tested against the Nardin and the Waltham. As it happened, the Japanese watches got clobbered by the foreigners.

The judges noted in their final report that the Japanese timepieces were below foreign standards. “Some showed a difference of three minutes a day, and even the same model watch, depending on the product, exhibited a wide range of error.” As an example they cited the results of the test with watches in the vertical position with the crown facing up. The average daily difference of the foreign watches was 4 seconds slow. The Seikosha watches varied from 6 seconds to 62 seconds slow. The Citizen watches were 48 seconds slow.

That the Japanese timepieces did not fare so well against the foreigners was not a surprise. Switzerland and the United States had a huge head start on Japan in watch technology. What was surprising, though, was that Citizen fared so well against Sekosha. That raised the eyebrows of the Japanese judges, according to Professor Uchida. “Viewing the [Seikosha] product as a whole in comparison with the pocket watches of the newcomer Citizen [Shokosha],” Uchida writes, “it is clear that Seikosha’s product performance and production techniques were not necessarily superior.”

Kamekichi Yamezaki had to be pleased with his watches’ performance. Citizen watches were the new kid on the block, still in the developmental phase, yet they held their own in tests against Japan’s watch leader. It was a good omen. His little experiment with watchmaking was bearing fruit. The first Citizen pocket watches went on sale the next year.

Wristwatches and war

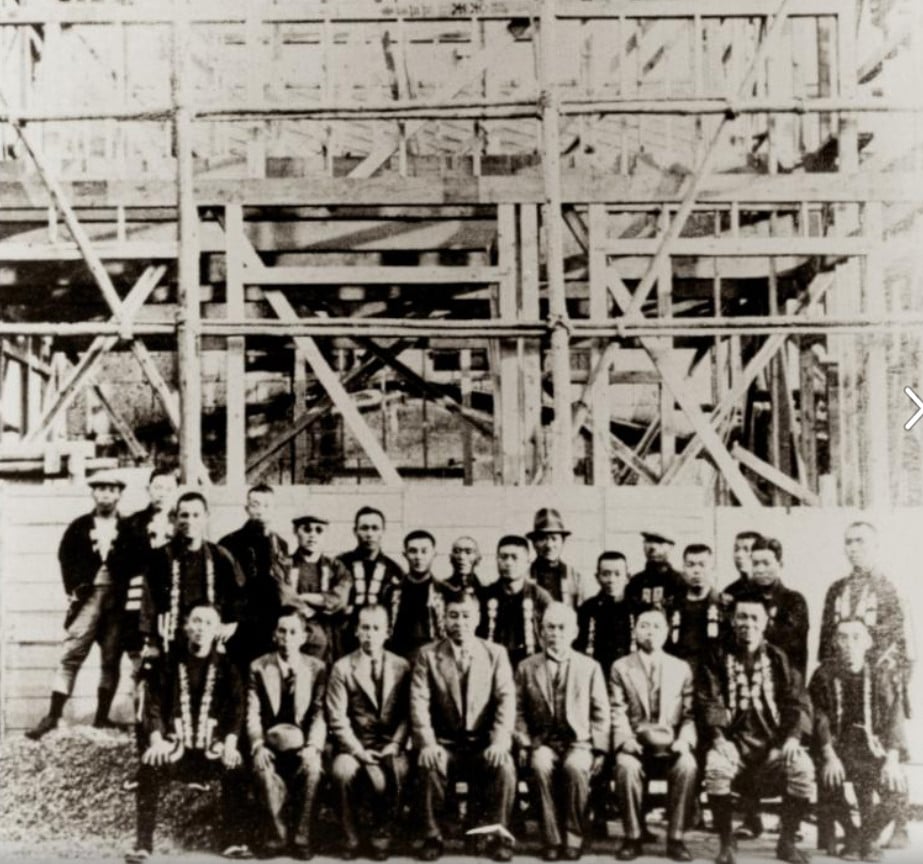

In 1930, the Shokosha Research Institute was reorganized and expanded into a full-fledged watch company. It got a new name, Citizen Watch Co. Ltd., and a new president, Yosaburo Nakajima. Kamekichi Yamazaki remained with the firm as director. Under Nakajima, the company began to emerge as a significant watch producer. In 1931, it began serial production of wristwatches, putting its F caliber 10-ligne manual-wound movements in both round and tonneau-shaped cases. In 1935 it introduced the 8-ligne K Caliber.

The next year Citizen opened the Tanashi factory in Tokyo, and it remains a key production facility to this day. With its production increasing, Citizen began exporting watches to Southeast Asia and the South Pacific region in July 1936. The 1930s marked an important growth phase for Citizen and the Japanese watch industry during which its watchmaking roots became firmly planted. In 1939, Japan’s total watch output passed the 5-million-unit mark for the first time.

Sadly, the Japanese watch industry’s progress was soon halted and Citizen entered the third phase of its history: war time. World War II caused a severe interruption to all the world’s watchmaking powers, save one – neutral Switzerland. Watch producers in the United States, Japan, and Germany went onto a war footing, shifting production to military timepieces, fuse mechanisms and other timing devices for the military. For the Japanese watch industry, the war was devastating. Another 20 years would pass before Japanese watch production again reached 5 million units.

During the war, Japanese watch firms shifted production from dangerous Tokyo (Citizen and Seiko factories were damaged by Allied bombs) to the relative security of the Japanese Alps. Citizen opened a facility at lida in Nagano prefecture in the Alps. The original lida factory is still in operation today and has been declared a historical building by the city fathers. (Citizen has mixed feelings about the honor: it would love to update the building but cannot because of the historical building designation.)

The Yamada era

In the two decades after World War II, Citizen planted the seeds that would turn it into a global watch power. The fourth phase of Citizen’s history lasted from the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s. The architect of Citizen’s post-war growth was Eiichi Yamada. He was 38 years old when he became president of Citizen in March 1946 and served in the post for 35 years. By the time he handed over the presidential reins in 1981 and moved up to become chairman, Citizen was firmly established as an international watch powerhouse.

Yamada understood that Citizen’s future lay in overseas expansion. In 1949, he created a separate sales and marketing subsidiary, Citizen Trading Company, charged with selling and marketing Citizen products on world markets.

In the 1950s, Citizen continued to develop its watch technology, attempting to close the gap with Switzerland, which had emerged from World War II in an even stronger position. Citizen displayed its growing prowess in mechanical watchmaking in a series of watches that were breakthroughs for the Japanese watch industry. Citizen introduced Japan’s first calendar watch (1952), its first shock-resistant watch (1956), its first alarm wristwatch (1958) and its first water-resistant watch (1959).

Parashock, the shock-resistant watch, was a sensation in Japan. In the summer of 1956 Citizen staged a series of demonstrations showing just how shockproof the watch was. While thousands of people looked on, Citizen dropped the watch from a helicopter. Amazingly, the watch survived the fall and kept on ticking. That’s because Parashock was equipped with a patented Citizen safety device that protected the sensitive pivots of the balance. Citizen dropped Parashock from helicopters in front of the Kyoto train station, at baseball games and various other venues around Japan. The watch worked every time. The stunts were marketing triumphs and boosted the public’s awareness of and trust in Citizen as a watchmaker.

Citizen staged similar events later with Parawater, the water-resistant watch. For its Trans-Pacific Test in the summer of 1963, it placed 130 Parawaters in specially designed buoys and tossed them from the deck of a ship into the Pacific Ocean. Ocean currents carried the buoys and exposed watches all the way to the North American coast. The trip took about a year. When the buoys were retrieved, the watches were still working, thanks to Citizen’s waterproof “O” ring and its self-winding Jet Rotor, which wound the spring in response to the action of the waves.

Citizen unveiled the Citizen Alarm, Japan’s first alarm wristwatch, in 1958. Equipped with a manual winding caliber A-980, the watch had a second crown for setting the alarm time and a reminder disc in the center of the dial. That year Citizen also introduced the company’s first automatic movement, Caliber 3 KA, with 21 jewels.

By 1959, thanks in part to the strides Citizen was making, Japanese watch production rebounded to pre-war levels. Total watch production reached 5.45 million units, surpassing the 5-million-mark for the first time since 1939.

In the late 1950s, at Yamada’s urging, Citizen began a vigorous program of international outreach. In a seven-year stretch between 1958 and 1965, Citizen laid the foundation of its global watch empire. It began exporting watches to China in 1958. In 1960 it began a technical assistance agreement with India that helped bring watchmaking to that country. Former Citizen Watch president and chairman Michio Nakajima considers the technology transfer deal between Citizen and the Indian government a turning point for the company, giving the firm the confidence to do business abroad.

The same year, 1960, brought another turning point. In March Citizen entered an import-export agreement with Bulova Watch Company of the United States. Bulova was at the peak of its power, about to introduce Accutron, the world’s first electronic watch. Under the arrangement Citizen supplied watches and movements to Bulova (for its affordable Caravelle line, for example, which Bulova introduced in 1962 as a jewel-lever alternative to pin-lever watches then on the market.)

The deal was a boon for Citizen’s fledgling movement and private label watch business. By 1970, about two million Citizen movements had gone into Caravelle watches. But it was a two-edged sword. Under the terms of the deal, Citizen agreed to stay out of the U.S. Market so as not to compete directly with Bulova. By the time the deal ended in the mid-1970s and Citizen finally entered the U.S. Market, its Japanese archrival Seiko had a huge head start in the lucrative American market.

There were no such barriers in Europe. In 1965 Citizen opened an office in Germany and began full-scale watch exports to European markets.

The electronic age

The debut of Bulova Accutron in October 1960 was a turning point in watch history. Accutron was the world’s first electronic watch. It employed a new type of time technology that made it far more accurate than a traditional mechanical watch. Accutron was literally a child of the space age. Bulova had been supplying special “tuning fork” timers to the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA) for use aboard satellites. The timers were powered by electricity. Their time base, or oscillator, was a tiny Y-shaped piece of nickel alloy, which hummed as it vibrated, leading to its designation as a “tuning fork”. By installing the same tuning fork technology into Accutron, Bulova created the world’s most accurate watch and launched a new era in watchmaking: the electronic era.

Bulova’s breakthrough presaged the end of the mechanical watch era. It dispensed with the hairsprings and balance wheels that had regulated watches for 400 years. For mechanical watch leader Switzerland, electronic timekeeping represented a threat. For American and Japanese watchmakers, it represented an opportunity. In the 1960s, watchmakers in all three countries rushed to master the new technology.

In 1964, Citizen opened the Tokorozawa Technical Laboratory, a research and development facility created specifically for electronic watches. Within two years Citizen began producing the X-8 series of electronic watches. The X-8 went on sale in March 1966 and was Japan’s first electronic watch. It was powered by a silver oxide battery and controlled by a transistorized circuit moving with a balance wheel (Caliber 0800-25J). It ran for a full year without stopping. In an era dominated by automatic mechanical watches, this was a major advance. Moreover, its striking design earned it Good Design Award from the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI).

The success of the X-8 brought a burst of confidence to Citizen. Seven months after the release of the X-8, in an article in Tokyo’s Asahi Evening News, Yamada made an astounding prediction. He asserted that Japan, which had produced 13.6 million units the previous year versus Switzerland’s 55 million, would surpass Switzerland in watch production within five years. Yamada sensed rightly that electronic watch technology would shift the balance of watch world power Japan’s way. Japan would eventually topple Switzerland, but it would take longer than Yamada imagined, 10 years longer.

Citizen followed the X-8 with the X-8 Cosmotron in 1967, a man’s transistorized watch with four magnets on the balance and two fixed coils. Citizen sold that movement to about 20 foreign companies, including Bulova, which used it in Bulova watches. The X-8 series is also notable for a watch that was one of Citizen’s first world firsts. In May 1970 Citizen marketed the X-8 in a titanium case, the first-ever titanium watch. The company pioneered the use of the ultra-durable, ultra-light metal in timepieces and went on to become the world’s largest manufacturer of titanium watches.

In 1971, Citizen introduced the Caliber 3700 Hi-Sonic, Japan’s first tunning fork wristwatch, using technology acquired via its close relationship with Bulova. That year Citizen produced a record 8 million watches and movements.

Citizen’s surge

The first great leap in watch accuracy came at the start of the 1960s with Bulova’s Accutron. The second great leap came at the start of the 1970s with the arrival of quartz watches. The oscillating quartz crystal brought unprecedented accuracy to watches, to within one second per week versus one minute per week for a mechanical. Citizen entered the quartz age in 1973 with the Citizen Quartz Crystron, its first quartz analog watch. Its first digital watch, the Quartz Crystron LC, came in 1974. It was the first LCD (liquid crystal dispaly) watch to show the time, day and date. The ladies’ version was Japan’s first women’s LCD watch.

In the mid-1970s, Citizen’s 10-year investment in electronic watch technology that began with the Tokorozawa Research Laboratory began to pay off. For the next seven years, from 1975 through 1981, Citizen unveiled a new world’s first watch every year . That streak solidified Citizen’s credentials as one of the world’s premier watch producers.

The streak began in December 1975 when Citizen marked what was at the time the world’s most accurate watch. The Quartz Crystron Mega was the first quartz watch with a frequency of 4,194,304 Hertz. The extraordinarily high frequency made it accurate to within 3 seconds a year. The Mega was well named. In addition to being mega-accurate, it was mega-expensive. Citizen produced a limited number in solid gold cases and bracelets at a retail price of 4.5 million yen each.

The Mega was indisputable proof that Citizen and Japan had moved to the forefront of watch technology. Ever since Japan began watch production in the 1890s, it had labored in Switzerland’s shadow. Initially Japan was about 300 years behind Switzerland, which first made pocket watches in the second half of the sixteenth century. By 1958, when Citizen unveiled its first automatic mechanical watch, Japan had narrowed the technology gap to about 30 years. Now the gap was gone. Electronics had leveled the playing field. In the brave new world of quartz watches, Citizen was a leader.

Citizen’s next breakthrough involved solar power, something Citizen engineers had been experimenting with for several years. A pioneer in the application of solar power in timepieces, it developed a prototype of a solar powered analog watch in 1974. However, the cadmium battery was too expensive to allow commercial production.

The engineers kept working on it and shifted to a silver oxide battery. In 1976, Citizen unveiled the Crystron Solar Cell, the world’s first solar-powered analog quartz watch. The dial featured a bi-lingual day-date display and eight solar cell panels. Its movement (Cal. 8629-7j) was accurate to within 15 seconds a month. The suggested retail price was ¥45,000. The Crystron Solar Cell was far ahead of its time. While solar watches were not a big hit in the 1970s, Citizen’s ongoing research into light technology would yield a huge payoff two decades later with the company’s revolutionary light-powered Eco-Drive technology.

In 1978, Citizen started what came to be known as ” the thin watch wars”, one of the most memorable chapters of the quartz watch era. It involved a direct clash among the watch world’s three great producers of quartz movements: Citizen, Seiko and Switzerland’s ETA. The thin wars created headlines around the globe, raised awareness of quartz watches, especially Japanese quartz watches, to new levels, and launched a new watch look: thin was in.

Citizen started the war in May with the Citizen Exceed Gold watch, also known as the Citizen Quartz 790. It contained the world’s first watch movement thinner than 1 millimeter. This product of Citizen’s in-house R&D measured 23.7 mm x 20.0 mm x 0.98 mm. The thin movement enabled Citizen to use an ultra-thin case. The entire watch was just 4.1 mm thick.

Within months Seiko responded with an even thinner watch. The new ultra-thin watches from Japan captured the public’s imagination and symbolized Japan’s emergence as the leader in the new quartz technology. With Switzerland’s reputation as a watch leader on the line, ETA SA initiated a crash program to develop the thinnest watch and answer Japan’s challenge. In January 1979 ETA unveiled the Delirium, the first watch to break the 2 mm barrier. The entire case was a remarkable 1.98 mm thin. Japan responded with even thinner watches. Ultimately ETA won the battle with Delirium IV, a museum piece measuring 0.98 mm thin. (Delirium IV proved that, unlike a lady, a watch can be too thin. Its thinness made it literally unwearable. Strapped on a wrist, the wafer-like case and its movement bent so that it didn’t work properly.)

Switzerland won the thin-watch battle. But Japan won the quartz watch war. In 1981, the year after ETA unveiled Delirium IV, Japan topled Switzerland as the world’s watch production leader. Japanese production soared 23% that year to 108 million pieces. Swiss watch production fell 13% to 76 million. Eiichi Yamada’s prediction of 1966 had come true. For its part, Citizen’s output that year reached 35 million units.

For Yamada, it was all enormously satisfying. He took over Citizen when it and the Japanese watch industry were flat on their backs in the ashes of World War II. Now they were on top of the watch world. (An event in Hong Kong in 1982 symbolized Citizen’s new status. In October the world’s largest neon sign was installed atop a building overlooking Hong Kong harbor. The name in the neon lights was Citizen.) Yamada’s work was done. In 1981 he resigned as Citizen president and moved up to become chairman.

Global watch powerhouse

Yamada’s successor as president was Rokuya Yamazaki, grandson of Kamekichi Yamazaki, founder of the Shokosha Watch Research Institute. He himself would be succeeded as president in 1987 by another grandson of another Citizen founder, Michio Nakajima. (The Yamazaki and Nakajima families remained active in the company since its founding and members of both families still serve in the company.) Those two and Hiroshi Haruta, who succeeded Nakajima in 1997, have overseen Citizen’s spectacular growth over the past two decades into a global watch powerhouse.

In the mid-1980s Citizen and Seiko competed for the title of world’s largest watch producer. In 1986, Citizen took the title and kept it for the rest of the century. That year it produced 80 million watches and watch movements, accounting for 41% of Japan’s total watch output. Through its private label watch and watch movement divisions Citizen suplies watches and movements to watch companies around the world. Citizen remains discreet about which brands use its movements, but they include some of the world’s bestknown names.

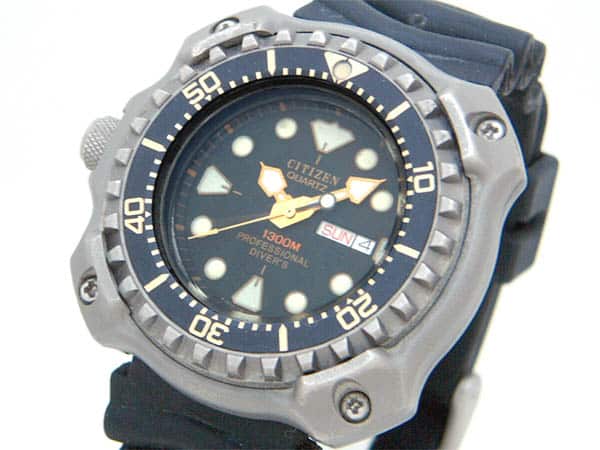

In the 1980s and 1990s, Citizen developed the distinctive features of the watch colossus that we know today. In the 1980s it introduced the first of its popular Aqualand series of divers’ watches. The first Aqualand in 1985 was the world’s first divers’ watch with an electronic depth meter. Around the same time, under the leadership of Laurence Grunstein, it began to make headway in the United States market that would make the U.S. Citizen’s top overseas market.

Later in the decade it introduced Altichron, the world’s first climbers’ watch with elevation sensor. The ProMaster series of sports watches came in the early 1990s. In 1995 came Eco-Drive, Citizen’s most important and successful product launch ever. Eco-Drive watches take quartz technology to the next level by solving the problem that has plagued quartz watches since they debuted: the never-ending need to replace the battery. Citizen’s Eco-Drive technology eliminates that need because the watches are powered by natural or artificial light. Exposure to any light automatically regenerates the battery.

Meanwhile, Citizen has continued to set watch production records. It bacame the first watch company to pass the 100-million-unit mark in 1988, the 200-million-unit mark in 1993 and the 300-million-unit mark in 1997.

Today Citizen is one of Japan’s largest industrial groups, with 80 companies spanning five continents. Annual revenues in fiscal 2001 amounted to Y393 billion ($3.27 billion). Besides watches, it manufactures a variety of industrial machines and electronic products, the result of a diversification policy from its core watch competence it initiated in the 1960s.

Watchmaking, of course, remains a core business, accounting for 45% of total revenues. Today Citizen produces one of every four of the world’s billion-plus watches and movements made each year. Citizen continues to explore new frontiers in watch technology. In recent years its R&D department has unveiled ahead-of-their-time timepieces employing new technologies like radio-controlled atomic timing and watches powered by body heat. Its stated mission is inspired by and remains true to the notion Tokyo mayor Shinpei Goto had in mind when he coined the brand: “to be close to the hearts of people everywhere.”